WEST episode

Season 17 Episode 2 | 55m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

WEST celebrates the continuum of heritage and the handmade in the American west.

WEST celebrates the continuum of heritage and the handmade, taking inspiration from the landscape, history and culture of the American West. Working across cowboy arts, Hawaiian indigenous practices, and Native American handwork, the artists show how traditional craft can be revived, reworked and reinvented in the art of today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

WEST episode

Season 17 Episode 2 | 55m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

WEST celebrates the continuum of heritage and the handmade, taking inspiration from the landscape, history and culture of the American West. Working across cowboy arts, Hawaiian indigenous practices, and Native American handwork, the artists show how traditional craft can be revived, reworked and reinvented in the art of today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Craft in America

Craft in America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Education Guides

Download Craft in America education guides that educate, involve, and inform students about how craft plays a role in their lives, with connections to American history and culture, philosophies and science, social causes and social action.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ Man: The saddle is the singular symbol of the whole myth of the cowboy.

We are all hardwired to do things with our hands.

The work of our hands is informing the work of our mind.

♪ Second man: It's really rewarding that I get to take part in something that is, like, quintessentially Texas, which is making cowboy boots.

I'm thinking about this as if this pair of boots is gonna be around for the next hundred years.

I'm gonna take kind of as much time as I need to to make the best boots that I'm excited about.

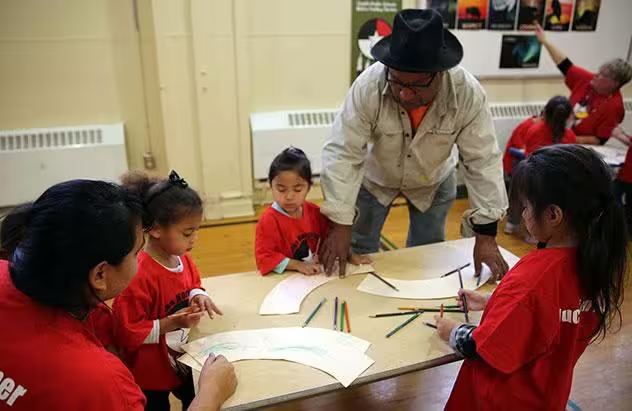

[Drums beating and people chanting] Third man: Here at the Institute of American Indian Arts, we offer degrees in contemporary indigenous arts, and that's unique to the world.

Woman: Ooh.

It is something amazing to be around other indigenous artists, to be able to speak art and breathe art with them.

♪ Fourth man: Doing Hawaiian feather work, I started understanding the ingenuity and the craftsmanship of our ancestors.

[Man singing in native language] Fifth man: In the seventies, there's no teaching the Native Hawaiian language and culture.

But there was a movement that started called "The Hawaiian Renaissance."

And then there was this idea of building a traditional voyaging canoe.

That became the flashlight that helped our people get out of the dark of the storm.

♪ [Theme music playing] ♪ ♪ ♪ I was 19 years of age when I first made my entry into the world of horses and mules.

♪ There is nothing like experiencing that sagebrush sea, as it were, on the back of a horse.

♪ And it's all those things that we consider the spirit of the cowboy, that freedom, independence, and "I'm kind of making my own way in this world."

That's all part and parcel of that experience.

♪ The saddle is the one singular symbol of the whole myth of the cowboy.

It's a tool, but it's also an enormous cultural symbol.

♪ Steven: Cary Schwarz is the top of the game of saddle making.

Like everybody, he started off making saddles for working cowboys.

But he is very much an artist.

He has helped to elevate the cowboy arts to collector-level.

The cowboy arts originally were just the equipment they need to ride a horse and to work on a horse.

They were miles from nowhere and didn't have stores to go to and replace their broken ropes and horse tack.

So, they had to make them.

♪ And if you have to make your own saddle, you might as well make a pretty one.

♪ Cary: I chose saddles because it represented the supreme challenge.

All of the things to understand about leather, from function to the artistry, are represented in the saddle making trade.

[Grinder whirring] [Grinder slowing to a stop] Leather engages pretty much all of your senses.

I just love the aesthetics of it, the feel of it, the versatility of it, the smell of it.

It's just intoxicating for me.

Most of our saddle leather is from Hermann Oak Tannery in St.

Louis, a family business since the 1880's.

What they've used for many years is an extract of bark from the mimosa and kibrahacha trees, and it secretes tannins.

Well, those tannins are what preserve the leather.

The structure of a saddle consists of a saddle tree.

It's a framework that is internal in the saddle.

I source my saddle trees from a one-man shop in New Zealand.

So, it starts out with that.

And what we call the ground seat is the layers of leather that are sculpted onto the saddle tree, where the person actually sits.

[Scraping sounds] If you can combine a good-quality saddle tree, a good-quality rigging, what actually holds the saddle on the horse, and a ground seat, if you have those three elements, you've got a usable saddle.

What we're after here is smooth transitions.

So we want this element to blend smoothly into this shape right here.

I've got what we call a Chase pattern splitter, and it makes thick leather thinner.

[Tearing sounds] Leather gauge.

Saddle making, like any other craftsmanship, is sequential.

What we're doing now is setting the stage for the next step.

[Hammering sounds] Now... this creates a tunnel for those stirrup leathers.

From here, I just keep layering pieces, sculpting.

I want to make it into a shape that is conducive to the comfort of the rider.

[Gate creaks] ♪ Roy has been my companion now for about 20 years.

♪ We do ask certain things of the horse.

There has to be a respect relationship.

If you don't have that, you're asking for trouble.

They are looking for comfort or safety, and if you can give that to them, then you have a foundation where you can work together.

♪ In our trade, we hold very dear the handmade quality of what we do.

[Hammering sounds] The cowboy world very much subscribes to that hand-built view.

♪ We are all hardwired to do things with our hands.

That's how we learned as children.

We just did it and failed over and over and over again, and, of course, as adults, we want to short-circuit the failure part of it as best we can.

It's literally learning by doing, and the work of our hands is informing the work of our mind.

♪ I've studied the function of a saddle till I'm blue in the face, but the artistry part of it I've invested a lot in.

With floral carving, we start with a swivel knife, and then we take a series of tools that make different impressions and textures in the leather.

[Hammering sounds] What we're trying to do is to manipulate light and dark and come out with a three-dimensional quality to create a saddle decorated in ways that can enhance people's lives.

[Loud bang] ♪ Back in 1998, the seed was planted for the group that would become the Traditional Cowboy Arts Association.

We exhibit every year at the National Cowboy Museum.

The work is within four disciplines-- rawhide braiders, and silversmiths, bit and spur makers, saddle makers.

♪ Our organization gives out two fellowships a year, where up-and-coming makers can come and spend time with members, and this is how we preserve and promote these cowboy trades.

♪ ♪ Craftsmanship comes down to, I think, a pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty... something that people can hang onto and find fulfillment and enrichment.

♪ Truth, goodness, and beauty... that's really what I'm trying to do today.

♪ ♪ Dr.

Martin: The central focus of the campus here at the Institute of American Indian Arts is our dance circle.

The four cardinal directions, solstice, and equinox are marked.

Then the campus buildings radiate out from that.

If you look out to the east, you can see all the way to the sunrise.

That's important.

That's how we start our day, and that's when we have the most energy, and I get a sense of the sacredness of the campus.

Teri: This is actually an international school.

We are different nations.

We are not all "Native American."

We are Kiowa, Comanche, Seminole, Chumash.

We speak different languages.

Our spirituality is different.

We are different Native nations.

Rose: The school considers background and considers cultural identity and considers post-colonial stress disorder when it comes to students and our artistic expressions.

♪ Deb: The college attracts indigenous students from across the country and Canada as well.

It's important that students have an opportunity to really hone their creativity, um, from all of their different communities and cultures.

Man: It was hard at first to do the cast, the metal cast for the bolo, because it was too thin.

And we didn't have the right size box to do the cast.

So, it wasn't coming.

Keri: Native people have been making things and adorning ourselves since the beginning of time, adorning every object in our lives.

Everything is imbued with imagery and story and connections to our surroundings, to each other.

And that is the very core of what craft is.

And just about every student who comes in here already has that knowledge because they've grown up in an Indian family.

I came to IAIA with the knowledge of my own tribe's really rich silversmithing history.

But the techniques that I learned at the school were more contemporary techniques, basic jewelry skills-- casting and different types of fabricating.

You can't build a house without a foundation, right?

[Hammering sound] Kayla: I knew I just wanted to become an artist.

I wanted to explore every little thing.

I'm very much a jack of all trades.

So, when I came to IAIA, you know, put all my effort into it.

My exhibition is about the ancestral teachings that come from our grandparents, our great-grandparents.

These are stars that they... They offer guidance to my people.

They show us when we have our ceremonies, what time of year it is, what season we're in.

They guide us.

Then you look in the portal.

You see yourself in those stars.

It is something amazing to be around other indigenous artists, to be able to speak art and breathe art with them.

We can make art and use iconography from our tribes or just different values that we put into our work that is just understood.

Dr.

Martin: That's a value, I think, to have indigenous voices there in terms of the faculty and staff and other students who understand that indigenous perspective.

Those are guiding principles from the original founders of this institution.

♪ IAIA was founded in 1962.

We started as a BIA school, the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Of course, the purpose of most BIA schools was to assimilate the indigenous students.

But here, it was different.

It was Lloyd Kiva New's vision and philosophy that's the foundation for the programming here.

Students brought their traditions and histories and cultures to us.

And then they were able to innovate with their creative expression beyond the boundaries of traditional indigenous art.

So, as a result, we became the birthplace of contemporary indigenous art.

♪ Terran: Being here really opened my eyes to what art could be.

I was able to see that there's actually all sorts of mediums and styles.

And geometric abstraction is something I was really drawn to.

♪ My current studio practice is ledger drawing.

With ledger drawing, our foundation to draw on is antique ledger accounting sheets from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

Our traditional ledger art is very figurative.

It's very representational.

There are a lot of people, horses, ceremonial scenes.

I grew up seeing my father work.

He does traditional ledger art.

So, that's why it's important to me.

It's because of my family.

It's because it's a way of recording our history.

♪ A lot of the geometric forms I'm using are directly influenced by Blackfoot painted lodges.

We had a lot of geometric symbols symbolizing mountains, sun, moon.

So, I'm continuing these geometric forms that have been here in North America for thousands of years, but in a modern way.

♪ Laine: What you see here is one step in the process of Chilkat weaving, taking the guard hairs of the janwu, the Alaska mountain goat, and then processing it down into the point where one can spin with it.

The janwu comes from the top of the mountain.

And I really, in my own personal practice, view it as being this sort of spiritual being.

And so, being able to work with it in this regard is, I think, just a huge honor for myself, um, just to process it, to, you know, kind of have good intention when you're working with it.

It's just highly important.

Chilkat weaving is a way to tell a story, a way of honoring tradition, clan histories, a way of connecting ourselves to the land that we're from.

Connections like that really kind of keep the momentum going and the inspiration.

♪ Pat: IAIA really is a hub of creativity that really is unfettered.

As a professional metalsmith who has been successful with my career, I had a pretty robust skill set.

But being exposed to all these different mediums, like printmaking, jewelry, sculpture, photography, this school has really enabled that exploration of different disciplines.

And I'd like to say the medium finds you.

I ended up having an emphasis in ceramics, which is really fascinating, considering that the pueblo that I come from, we are known as potters.

We're not known as jewelers.

That just kind of came out, and there was a connectiveness that's there.

♪ I think it's just kind of inherent within the Native culture that the skill set and the talent is in the arts.

And so the craft or the art is passed on from one generation to the next, and it becomes part of who they are.

Linda: It's important for me to pass on to my students to be proud of who you are and know your cultural ways and use that to create.

[Drumming and chanting] Dr.

Martin: There's a community here at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and the commencement ceremony, that's where it's the most beautiful.

We offer degrees in contemporary indigenous arts and cultures, and that's unique to the world.

[Cheering and applause] Linda: The student represents their tribal identity.

They become ambassadors of their tribe.

You're not just artists or writers or filmmakers.

You are cultural stewards.

Thank you all so much.

Congratulations.

And be fierce!

[Loud cheering and applause] Linda: When they go back to their cultural communities, they carry on that, the legacy of what IAIA has taught them.

[Drumming and chanting] Teri: What we do, as Native people, those words that we use for what we do, we're makers.

[Bells jingling] Being with a community of other Native peers, all learning and experiencing this, making such beautiful work, so inspired, and just the interconnectivity that we have, that's all we have as human beings.

♪ Keri: IAIA is a place that is in between that contemporary art world and rooted in traditional values and traditional work, and it's a way for us, as Native people from all different walks of life from the city and from the res and from just down the street and from all different ways of seeing the world.

There's that underlying core of Nativeness that pulls us together.

[Chanting] Rose: As with any community, you give, but you also receive so much inspiration and excitement about what's possible.

The more that the Native arts community can collaborate and communicate and address issues that are present in our world, in our life, the better, right?

♪ Graham: I love Texas.

It is all about the wild frontier... and all about opportunity.

♪ Austin is a great place to live.

It's got great food, great music.

It's an incredible spot to be an artist.

There are folks over here on the east side doing everything from painting and illustration to ceramics to leatherwork.

♪ It's really rewarding that I get to take part in something that is, like, quintessentially Texas, which is making cowboy boots.

♪ Cowboy boots have always been an expression of personal style.

Folks, for a long time, have made cowboy boots with traditional imagery, whether it was, like, top stitching or flowers... cactus, things like that.

I wanted to make cowboy boots, but I wanted to draw, and I wanted to take things that you might find in the West, whether it's palm trees from California or, you know, scenes from a national park, do a little bit of storytelling, something that allows me to put my own spin on it.

[Birds chirping] I did a pair that have an image of Santa Elena Canyon in Big Bend National Park in West Texas.

You have, like a pretty peaceful scene on the front, right?

We have your good-luck horseshoe.

It's, like, a beautiful blue sky, sunny day.

And then we've got a prickly pear cactus.

We've got an armadillo hanging out here in the foreground.

Got the river flowing right there.

Um, and then we turn it around, and things have changed a little bit.

Like, our UFO that was up here kind of hiding has come down, taken the armadillo for a spin.

But he looks pretty happy about it, honestly.

And the prickly pear cactus have turned into magic mushrooms.

♪ I am making just a few pairs of incredible-quality, creative boots a year.

A basic pair for me takes about 150 hours.

If it's a complicated pair and has a lot of inlay, it may take me 250 hours to make the actual boots.

This is all techniques that have been passed down or slightly modified by one person and then passed down to an apprentice.

It takes a lot of years of learning how to do it before you can do it really well.

[Motorcycle engine rumbling] I have one customer named Blake.

I made him a pair a couple years ago.

I love the way that he interacts with his boots.

♪ Blake: There are certain timeless things-- a white t-shirt, blue jeans, and cowboy boots.

They fit the mold throughout the decades.

So, when I saw Graham's boots, I was like, "Man, this guy has got the style for sure."

Graham: Okay.

So, we're thinking about making another pair.

You've been wearing these for a while.

Is there anything that you would change, like, anything that was feeling a little funky or tight, anything like that?

Blake: No.

Honestly, no.

They've been flawless.

Graham: That's got so much good patina on it, a couple of good scuffs and scrapes and whatnot.

There is a soft spot in my heart for people who are gonna wear them and, like, wear them out.

Blake: I've worn them to weddings.

I've worn them to dances.

I've worn them to camping.

I've worn them on my motorcycle, on trips.

I've worn them in the garage, and, yeah, I will wear them for everything literally.

Literally.

Ha ha!

[Scraping sounds] Blake: You get tired of messing with feet?

Graham: Sometimes.

I think about feet a lot.

Okay.

Good.

Fitting someone's foot is the biggest challenge of this entire process, because a great-fitting pair of cowboy boots ought to feel kind of like nothing.

Like, they should be like a second skin on your foot.

All right, lift that one up.

I measure their feet, and I use that to build what we call a last for them.

All right.

So, this is somebody's last that I'm working on right now.

So, I'll build up the last where it needs to be larger.

I'll shrink it down in other areas if they need a little bit more support on the bottom.

And once that done-- is done, I'll move on to making their patterns.

So, I'll take something like this.

It's paper patterns.

Then I'll use this to actually cut the pieces out of the leather.

I've got, like, the front panel, which is comprised of, like, the tops, the vamps, which is the foot portion of the cowboy boot.

So, essentially, I make cowboy boots in two pieces, and then I take them, and I do what's called side seaming, which is just joining them to make the entire boot.

[Liquid spraying] This is a secret special stretching solution.

It's just water.

[Leather sliding] I really like to figure out a piece of artwork that I'm gonna put on top of a cowboy boot.

[Hammering sounds] But I also love the mechanical aspect of it, kind of the nuts and bolts of the construction part of the boot.

♪ My family has been here in Texas for a long time.

I grew up crafting and sewing and things like that.

My grandmother, Faye, she is a quilter.

I think she's made about 400 quilts, and she's in her nineties now.

So, I'd be at her house, and she'd be piecing a quilt, and I'd help her, you know, I don't know, start putting the batting on or maybe piecing some squares and working on, like, a little tiny quilt.

[Sewing machine whirring] She'd let me loose on the sewing machine so I'd be comfortable on that.

I don't think that I would be doing this without her.

♪ All of the inlay that I do is the same principle.

It's just like piecing a quilt.

I'm building up the scene with a bunch of different colored or textured pieces of leather to get the bigger image that I want.

♪ So, this is how to make inlay.

I drew this up in Illustrator and cemented the pattern on these.

I'll cut out the different pieces of this.

And then, using, like, different colors of leather, I'll fill in different shapes and then sew it all together.

I source leather from all over the world, from respectable tanneries.

My favorites are definitely kangaroo and calf.

Calf is the primary leather of pretty much any footwear in the entire world.

Kangaroo is a beautiful leather, and for inlay, it's a dream because it's strong, but it doesn't have a lot of thickness to it, like calf.

[Hammering sounds] This is the first step.

Essentially, it's like I have a main body, which is this kind of chocolate kip calf right here, and then I have one, two, three, four, five other pieces of leather.

I have two different colors that make up the actual eye itself.

And then, for the iris and the pupil, two different pieces of kangaroo, a chocolate brown and a black.

So, this is the first time that I had made myself a pair of, like, inlaid boots.

They were made with suede pig for the vamps.

It's very durable.

It's warm.

It's somewhat waterproof.

And then the tops are navy blue kangaroo, and then all the inlay-- little prickly pear spines, little flowers on the cactus, they're all kidskin.

I love these a lot.

What are you guys working on?

I moved into this shop last year.

I think it's a great thing to share space with Kathie Sever at Fort Lonesome.

Kathie: We make custom western wear involving chainstitch embroidery, working with clients to highlight their passions or their life stories that they want to narrate visually on their garments.

-Maybe this one?

-Yeah.

I like this one, too.

Kathie: Do it.

Graham: I love having this like creative camaraderie and then even have a little bit of crossover with the things that we do.

I had a customer from Northern California.

When she was a kid, her parents would take her to see Paul Bunyan and Babe.

It was, like, a 60-foot statue that was built in the sixties there.

And she said, "Oh, you know, I really want Paul Bunyan on my boots."

At first, I was a little skeptical.

It was just a little out of my wheelhouse, doing people, but we came up with something really creative and fun and a good opportunity for me to collaborate with Fort Lonesome.

We figured out a way to do a little bit of an embroidered inlay in and around Graham's leatherwork.

Graham: There's chainstitch embroidery, like on Paul Bunyan's chest hair and some, like, furry clouds up in the sky, too.

♪ I'm thinking about this as if this pair of boots is gonna be around for the next hundred years.

I want someone to find my work, maybe in a garage sale or an estate sale, and be like, "Wow!

Like, this is the quality of stuff that was being made back in 2025."

And so, like, I'm gonna take kind of as much time as I feel like I need to to make the best-quality thing that I can put my name on.

♪ [Waves crashing and seagulls squawking] Marques: The first voyagers to Hawaii traveled on double-hulled canoes, using the stars and the ocean currents as their guides.

But they used sails made out of woven pandanus leaves.

We call it in Hawaiian ulana lauhala.

And that was the material of choice to make our utilitarian materials from, the floor mats to baskets and containers.

But I think the settlement of Hawaii wouldn't have been possible without ulana lauhala.

♪ I remember, as a young boy, looking at my grandfather's lauhala hat and me trying to figure out how those little strips were interwoven into one another.

♪ So, this is the hat that inspired me to learn to weave.

[Marques singing in Hawaiian] The act of making is something that I learned from teachers and elders.

[Marques singing in Hawaiian] I also learned ceremonial practices associated with the art form as well.

So, when we go to a pandanus, we ask for permission of the plant.

We clean the tree, take off all the old leaves, and then we harvest the freshly dried leaves, because those will be nice and supple.

Mahalo.

♪ First, you would de-thorn the leaf, and then you would roll them into our rolls, called kuka'a.

♪ And then you would cut the prepared leaves into sized strips.

♪ And from that point, you would start to do your weaving.

♪ After learning the practice of ulana lauhala, I started to expand into cordage-making, into net-making, anything using fibers.

♪ I have created historical Hawaiian fans.

This style of fan was only used by the chiefly class within Hawaii, this crescent-shaped blade with this woven handle.

There's pandanus leaves for the blade, and there's coconut cordage along with hibiscus cordage that is an accent on the edge.

Just incorporating various techniques that really speak to the creativity of our ancestors.

♪ In Honolulu, I work at the Bishop Museum as the museum's cultural advisor and curator for cultural resilience.

The Bishop Museum was founded by Charles Reed Bishop to honor the legacy of his wife, one of our last Hawaiian chiefesses, Princess Bernice Pauahi.

All of her family's heirlooms passed to Charles, and Charles created the museum to safeguard those treasures, and today we have over 25 million specimens representing natural history as well as cultural materials.

♪ So, we have four different lei hulu, Hawaiian feather lei, using feathers from the endemic birds to Hawaii alongside a mahiole, a feathered helmet that was used by our chiefs to symbolize their status.

Kawika: Feathers adorned our ali'i, or our royal class.

They've stored or maintained mana, which is the spiritual essence or strength that you have within you.

And the mahiole belonged to King Kaumuali'i of Kauai.

All of the individual's mana resided in those physical pieces.

So, an item captured that spiritual energy, mana, of that person.

♪ Marques: Hawaiian feathered capes are known as 'ahu 'ula, and it refers to the ancestral capes that chiefs wore.

Kawika: No other 'ahu 'ula was made like this.

Marques: This is the only known Hawaiian cape that has upturned feathers of this type.

To get the feathers to stand this way and everything to be so uniform, it's very intentional that they collected without harming the bird, but just using what they need.

The amount gathered from each species is quite staggering.

To create something like this took a community of practitioners.

There would be bird specialists that knew where to acquire the feathers.

There's the people that knew how to prepare the netting, and then the skilled artisans that would combine all of those materials together.

Hawaiian forest birds are highly endangered.

So, I use feathers from birds that are food sources and other birds that molt.

These goose feathers can be harvested after they molt, and then we dye them in different colors.

This particular lei is called a wili poepoe.

The natural curve of the feather is coming away from the yarn.

But with the other style that we do make, the feather is the opposite way, which makes it very smooth.

You're doing thousands and thousands of feathers.

This is called a humupapa.

It's probably the more contemporary out of the lei styles for Hawaiian feather work.

It is made to go on a hat.

But for me, even in creating contemporary pieces, I like to remember that these were for our ali'i.

♪ If you don't tie on the same place every time, it will look like this the whole way down.

You have to be able to tie consistently every single feather.

I always try to get my students to think about how much it takes to be so accurate and so technical.

The edge of this feather should be in the middle.

That allows them to open their eyes to understanding the ingenuity and the craftsmanship of our ancestors.

I see you tried to do the no-crimp thing on the... I love to see that realization and that light bulb come on to them.

No, it's good.

♪ Marques: King Kamehameha I unified all of the islands together.

He did this through conquest and battle, becoming the first king of Hawaii in 1810.

Zita: This palace was completed in 1882 at the command of King Kalakaua.

He built the palace to send a message to the world-- "We're modern, we're educated, we're technologically advanced."

Construction here included telephones and gas lights, which were replaced by electric lights four years before the White House in Washington, DC.

Kalakaua died in 1891.

He had been traveling in the United States.

The Hawaiians did not know he had died until the ship he was expected home on was spotted off Diamond Head draped in black.

Marques: Queen Lili'uokalani was the heir to her brother, and during her reign, American businessmen overthrew the Hawaiian government.

Zita: She was deposed in 1893.

The provisional government took down the flag of the Kingdom of Hawaii and raised the American flag.

The Republic of Hawaii started arresting people, and then they arrested Lili'uokalani.

She was imprisoned in an upstairs room of the palace.

So, she began to speak to the future with thread and fabric, creating a quilt from garments, scraps.

The Hawaiian flag is very prominent in the quilt.

♪ It reminds us of who we were and what had happened to us and how strong she was.

♪ [Indistinct voices] Cissy: In Hawaiian tradition, you go, you sit, you watch, you learn.

So, if you don't mind, I'm gonna start you from the very beginning.

Cissy: My sister and I, we have an amazing Hawaiian quilting class.

It's a tradition that's almost four or five generations in our family.

[Indistinct voices] Rae: So, everything that you see here, all the Hawaiian quilts are one solid design.

It's not pieces put together.

It's just one piece, like you have here.

My role is to handle the beginners table.

We're gonna lay your pattern in place.

We're gonna pin it down.

We're gonna cut it out.

We tell them how to lay the pattern, how to cut it out, how to quilt.

And the ones who say that "I don't think this is meant for me," yeah, it is meant for you, and we will take the time to teach you how to do it.

Cissy: My sister and I come from a very traditional family, raised in the Hawaiian way.

My mom, Poakalani, was born with only one hand, and she was raised by her grandmother, and the grandmother would always say, "No, you can't quilt having only one hand."

But when her grandmother died, she had the dream where her grandmother came to her and says, "You need to look at my quilt patterns."

Then there were 200 full-size 90-by-90 quilt patterns.

My dad looked at that and said, "Well, why don't we reduce the pattern, make it into a smaller size?"

And then my mom was actually able to sew and quilt.

[Indistinct voices] When I started, she was teaching me, and she was amazing how she could do it with only one hand.

Pat: And she was like a force of nature.

She was so helpful.

And, of course, John, with all of these patterns... 90% of the quilts we have made are John's designs.

♪ Cissy: My dad, from the time that he was growing up, he wanted to be a cop because he loved to help people.

When he retired, he told my mom, "We're probably gonna want to start a quilting class."

He took his designs from culture, tradition, and from his background with flowers because his family were lei sellers.

And what's interesting is that he would draw only 1/8th of a full design.

He could actually see the full design by just drawing the 1/8th.

♪ He's drawn over 2,000 patterns.

And so we have this legacy to work through that is incredible.

I'm very grateful for it.

Make your stitches a little smaller if you can.

We have a table with people who graduate from the beginners table.

They still need a little help.

Then you have the third table, who are the ones that make these huge quilts.

Carla: We come to the table, and we help each other as we do our own projects.

So, it's like our own little family now.

Woman: I wanted the jellyfish in a solid color.

Maybe the ocean would be a little bit of a darker blue.

A dark blue.

So, we'll make it pop.

So, that's how you want to do the fish.

I had been thinking that I wanted a masculine quilt.

John and I started talking about the old Hawaiian warriors, and then he came up to me a couple weeks later, and he says, "Okay, close your eyes."

And he led me over to his desk, and there the pattern was.

I thought, "This is a political statement that he's making," because the warrior helmets are surrounded by the finials of the 'Iolani Palace, like keeping them prisoners inside.

The way I interpreted it was people from the mainland imprisoned the queen in the 'Iolani Palace and took over the islands.

A lot of the old ways were lost because of that.

Maybe John had that in mind.

Rae: Cissy and I never thought we would be the teachers, but my mom passed away in 2012, my dad in 2018.

Cissy: Okay, there you go.

That's good.

Rae: Cissy and I, we talked about, "What are we gonna do about the class?"

And we said, you know, all we can do is try.

That was the mission of my parents, to pass their culture on from generation to generation.

So, this is my grandmother.

She was taught by Poakalani.

I was seven years old, and my grandma would bring me every Saturday, and we started quilting.

She's done quilts for all of the grandkids.

So, she's doing a seahorse right now that John designed.

She wanted whale...whales.

Dolphins.

Ha ha ha!

-Dolphins?

-Ha ha ha!

[Laughter] Good job.

Thank you.

Thank you so much.

Am I proud?

Absolutely.

My dad said it's just a squiggly line on a piece of paper, but the quilters bring it to life.

They keep us going.

So, we do it for our quilters.

♪ [Shell horns blowing] In Hawaii years ago, you know, racism was here for sure, but it wasn't really addressed.

In the seventies, there's no teaching the Hawaiian language and culture in public schools.

I get out of high school, and I don't have no idea who my ancestors are.

I have no idea where they come from.

And I have no reason to be proud that they were the greatest explorers and navigators on the face of the Earth.

[Drums beating] But there was a movement that started called the Hawaiian Renaissance, and there was this idea of building a traditional voyaging canoe.

[Water splashing] That became the flashlight that helped our people get out of the dark of the storm.

♪ Lehua: This weekend, we are commemorating the launch of Hokule'a 50 years ago... ♪ An incredible event that changed the way we see ourselves as Hawaiians, our place here in Polynesia, in the Pacific.

♪ ♪ Nainoa: Hawaii is the single most isolated island archipelago on the planet.

And the Polynesians, 1,700 years ago, came across 2,400 miles of open ocean.

How did they get here?

Lehua: There had built up over time this idea that maybe they had simply drifted by chance and arrived here in Hawaii.

Nainoa: The existing knowledge was the voyaging canoes couldn't sail from west to east against the predominant trade winds.

Except there were these dreamers, and one was Herb Kawainui Kane.

He was a sculptor and a painter.

And along with Dr.

Ben Finney, who was an anthropologist, these two individuals brought together culture and traditions and science.

[Chanting] They made a quiet promise to build a voyaging canoe.

"Let's sail it to Tahiti, and let's set the record straight."

♪ Constructing the canoe.

They blended that traditional Polynesian understanding of the artistry of the canoe, and then they brought in marine science and engineering to make sure it could do this 2,400-mile voyage.

♪ [Speaking Hawaiian] Nainoa: The day of the launching, Native Hawaiians were there praying for the canoe.

It has to be successful for our people.

On board the canoe, it was Herb and Ben and Tommy Holmes, one of the top watermen in Hawaii.

[Speaking Hawaiian] Nainoa: And then we get alongside the canoe to push it down the beach.

[Man shouting in Hawaiian] [Onlookers cheering] And she went in the water so fast, I was like, "Wow!"

There's just this beautiful canoe.

God darn.

♪ Lehua: Hokule'a is about 62 feet long and about 21 feet wide.

She looks as much as a traditional ancient canoe as could be designed.

♪ She's also a sailing canoe, and that means that we need wind to power her sails... Man: Get ready.

Lehua: And so, she's double-masted.

The crew will rotate on three different watches, and when they're off watch, they will usually be resting in one of these bunks.

It's very simple.

We have hatches that store water and food beneath them.

Here we have the hoe uli, a very large paddle.

and it's got a very large blade that digs back into the water, and you actually will operate it by pushing the water towards the starboard side or towards the port side, and this will direct the course of the canoe as you're sailing.

But knowing where to go, that is the most important part of steering.

That is the job of the navigator on board.

Nainoa: Just how did the Polynesians navigate by the stars?

[Drums beating] The day she was launched 50 years ago, there was a Micronesian man.

We call him Mau.

He was a master navigator at a time when there was only six left.

Mau became the primary navigator and then the primary teacher for the next 28 years.

Lehua: When we're trying to find our way without a modern compass, without a GPS or a sextant, there are about 200 stars that we really focus on.

But stars are only visible maybe 10% of the time.

So, as we bring our gaze from the heavens, we come down to a very important element of navigation, which is the ocean itself.

You can see the patterns of the waves, waves coming from different directions.

How are they changing throughout the day or over the course of many days?

You're also relying on what kind of wave motion are you experiencing standing with your two feet on the deck.

The most advanced navigators are most in tune to those waves.

Nainoa: On May first, 1976, Hokule'a left.

The trip took 31 days to get to Tahiti.

♪ There were an estimated 17,000 Tahitians there.

That's more than half the population.

They were saying, "We're proud of this moment.

"This is our history, our legacy, our traditions.

This is our canoe."

♪ There was two crews.

One was to sail it to Tahiti, and one was to sail it home.

So, I was on the trip to come home.

I was really scared.

I spent my whole life in the ocean, but shallow water, coastal stuff.

Now you're gonna be in the deep.

♪ It took us 23 days to get home.

No storm, good winds.

We arrived, and there was this celebration of this amazing feat.

[Onlookers cheering] Announcer: The sound of "aloha" to welcome Hokule'a.

Nainoa: My grandmother was there.

She was so worried, but she knew I had to go.

She came up to me, and she just put her two hands on my face, and she looked me in the eye... ♪ [Drumming and chanting] Man: On this date 50 years ago, a dream came to fruition-- the initial crew that went down to Tahiti in 1976.

Many of them are here today.

They're the trailblazers that strengthen our connection to our indigenous roots of voyaging and navigating.

Announcer: How's about a big hand for all of these elders who made the dream a reality?

[Applause] So, the ways that we continue to honor them is by raising up and continuing to sail.

♪ Lehua: When this all started, there was the idea that she would only sail one voyage, and yet, 50 years later, she's actually circumnavigated the planet and has sailed hundreds of thousands of miles with hundreds of crew members.

We're only gonna be more and more off the wind probably.

Today, I am the first woman to lead, captain, and navigate the Hokule'a.

♪ Nainoa: In Hawaii, we were so crushed, our culture.

But Hokule'a opened that door to go and change things and be who we are, Native people, Hawaiian people.

♪ ♪ Stream more "Craft In America" on the PBS app.

♪ "Craft In America" is available on Amazon Prime video.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S17 Ep2 | 1m | Watch a preview of WEST, celebrating the continuum of heritage and handmade in the American west. (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by: